The language of Rumi and Omar Khayyam is on the verge of losing the battle for its survival at Peshawar University’s Persian language department.

The decline of the Persian language in Khyber-Pakhtunkwa (K-P) has been slow but significant. Once a mandatory subject at schools the language, known for its poetry, is no longer being taught and perhaps spoken as commonly as it once was.

The prominent plaque outside the Peshawar University’s once-bustling Persian language department might as well be its epitaph. Established in 1956, the department has no students and just one faculty member.

“From time to time, we translate land ownership documents in Persian for Jirga decisions,” said Dr Yousuf Hussian, the only assistant professor at the depleted Persian language department.

Four out of the five full-time faculty members have retired, leaving the department with just one assistant professor. Ironically, all four retired instructors, including the former head of the department, remain listed on the official website, which may have received update years ago.

Known for training prominent politicians and members of the academic community, the bare-bones department at the university only has one assistant professor.

With just one faculty member, who frequently juggles with both clerical and academic duties, the Persian language will soon merge with the Urdu and Arabic department. A sharp decline in interest in the language has also forced the department to freeze admissions this year. Not only that, the department has already halted all classes, leaving the once filled rooms with lovers of poetry attributed to Omar Khayyam and Rumi, empty.

Despite being abandoned, the language still has some purveyors. One such individual is Qazi Fazli Wahid, a 70-year-old gold medallist, who holds an MPhil from the University’s Persian department.

“This is the language of Sufism, Iqbal, and intellect,” said the septuagenarian.

“Not too long ago, schools across K-P taught the Persian language, and we had outstanding teachers in the province,” said Wahid, who has witnessed the rise and fall of the language.

“The Bustan and the Gulistan, a landmark of Persian literature, are no longer being taught,” Wahid added.

According to Muhammad Tayyab, a historian from K-P, the language witnessed a brief period of promotion after independence. “The language received a severe blow during General Zia-ul-Haq’s era. Propaganda at the time portrayed Persian as the language of Shiites,” Tayyab claimed.

Under Zia’s pressure in the late 1970s, the K-P Text Book Board, which is responsible for preparing curricula manuscript of textbooks, scrubbed Persian from its official menu of languages taught across the province. Persian never recovered from that fatal strike. And so began the final descent of Persian that once served as the official language of the Mughal court.

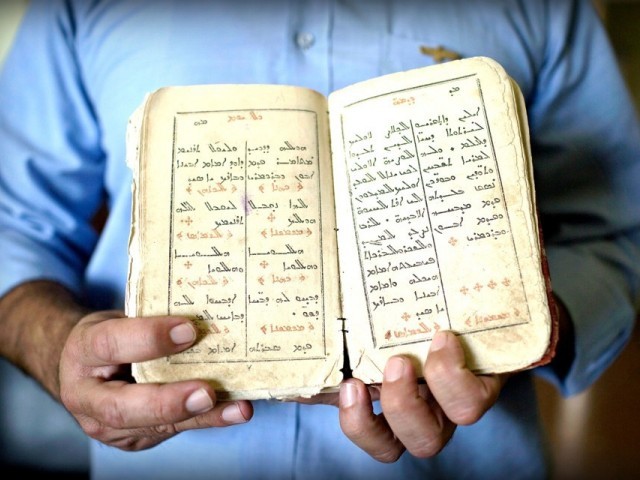

While the pluricentric language exists in subtle ways across the province, in ageing documents and books of poetry, it will perhaps never have the same status it once did. But Persian will always remain threaded almost invisibly through poetry, kept in shape by a combination of tradition and devotion, like good hand-stitching, by people like Wahid.

Published in The Express Tribune, November 27th, 2019.